Gastrointestinal tracts of domestic animals

Copyright 1996-2022 by Jeannette A. Moore. Permission is granted for anyone to use these images for educational purposes, provided that this copyright statement is kept with the images and provided that the images are given, not sold.

Note: These drawings have been intentionally simplified to aid in the learning process. Please also note that they are not to scale; the intestines are actually much, much longer in each species, and they curve around inside the animal’s body.

Video: There is a short (3 minute) video that helps to illustrate the similarities and differences between the three types of mammalian gastrointestinal tracts. After reviewing the information below, please see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J9tfZxBIec8

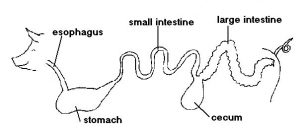

Monogastric Gastrointestinal (GI) tract:

Note: the pig is used as the example here, but all monogastric mammals are similar.

Functions:

Functions:

The esophagus transports feed from the mouth to the stomach. It is possible for material to go from the stomach to the mouth, but this is undesirable in monogastrics (vomiting).

The stomach secretes hydrochloric acid, which is a strong acid that begins chemical digestion and also kills bacteria. There is also an enzyme secreted here that starts breaking down protein, but this is not the main site of protein digestion (the small intestine is). Some stomach cells secrete a protective mucous to keep the stomach acid from harming the cells lining the stomach. If this damage occurs, an ulcer forms.

The small intestine is where most digestion occurs (by enzymes the animal secretes into the small intestine). These enzymes can digest (break down) starch, protein, and fats. Before the enzymes can do their job, the pH of the digesta has to be increased from the very low pH of the stomach contents; this is accomplished by buffers that are secreted by the pancreas into the first part of the small intestine. Important: The small intestine is where nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream. Any nutrients that are not absorbed into the bloodstream are lost in the feces!

In the cecum, fiber can be fermented (digested) by microbes. Swine in the U.S. are on low fiber diets, so this is not very important for their digestion. Dogs and cats have a very small cecum, and humans don’t have one at all. Horses and rabbits have a very large cecum; see the diagram below.

In the large intestine, some fermentation occurs by microbes that live in the first part of the large intestine. As material passes through the rest of the large intestine, water is absorbed back into the animal’s body.

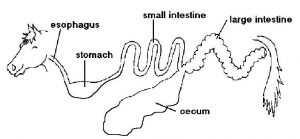

Special Monogastric Gastrointestinal (GI) tract: Horses and Rabbits

Note: the horse is used as the example here, but rabbits are similar.

Functions:

The esophagus transports feed from the mouth to the stomach. The horse cannot vomit, and its stomach is very small relative to the horse’s large size. This means there is a danger of the stomach rupturing if the horse eats too much feed all at once.The stomach secretes hydrochloric acid, which is a strong acid that begins chemical digestion and also kills bacteria. There is also an enzyme secreted here that starts breaking down protein, but this is not the main site of protein digestion (the small intestine is). Some stomach cells secrete a protective mucous to keep the stomach acid from harming the cells lining the stomach. Material does not stay in the horse’s stomach very long because the stomach is so small (only about 2 gallons in a 1,000-pound horse).

The small intestine is where most digestion occurs (by enzymes the horse secretes into the small intestine). These enzymes can digest (break down) starch, protein, and fats. Before the enzymes can do their job, the pH of the digesta has to be increased from the very low pH of the stomach contents; this is accomplished by buffers that are secreted by the pancreas into the first part of the small intestine. Important: The small intestine is where almost all of the nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream (read about energy produced in the ceum below). Any nutrients that are not absorbed into the bloodstream are lost in the feces!

In the cecum, fiber is fermented (digested) by microbes. Horses have a very large cecum because they eat high fiber diets. Horses get energy from VFA’s that are absorbed into the bloodstream from the cecum (see discussion above on the rumen in cattle). In the horse, the cecum is about 4 times as big as the stomach.

In the large intestine, some fermentation occurs by microbes that live in the first part of the large intestine. As material passes through the rest of the large intestine, water is absorbed back into the animal’s body.

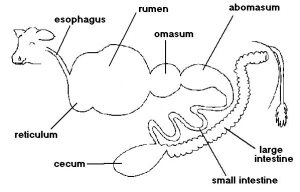

Ruminant Gastrointestinal (GI) tract:

Note: the cow is used as the example here, but all ruminants are similar.

Functions:

The esophagus transports feed from the mouth to the rumen/reticulum after the ruminant swallows. Later, the ruminant animal can bring material from the rumen back up the esophagus and into the mouth for more chewing. This is called ruminantion, and is sometimes referred to as “chewing cud.” Rumination is normal, and is not considered to be vomiting.Nothing is secreted by the animal into the rumen and reticulum, so these first two compartments do not have a low pH (are not acidic), unlike the stomach of a monogastric. In the rumen/reticulum, fiber and other feed components are fermented (digested) by microbes. Most of the microbes are bacteria, and they can actually break down the fiber. The waste products from the bacteria are called VFA’s (volatile fatty acids), and these are absorbed through the rumen wall into the animal’s bloodstream. These VFA’s provide energy for the animal to live on. The rumen/reticulum compartment is quite large, and can hold 50 gallons in a Holstein dairy cow!

The omasum is the next compartment. Water is absorbed from the digesta as it passes through the omasum.

The abomasum secretes hydrochloric acid, which is a strong acid that begins chemical digestion and also kills bacteria. The abomasum is comparable to the stomach in monogastric animals. The dead bacteria become a source of nutrients for the ruminant, and they pass into the small intestine where they are digested along with the remaining feed particles.

The small intestine is where digestion occurs (by enzymes the animal secretes into the small intestine) of everything except fiber that makes it this far in the GI tract. Before the enzymes can do their job, the pH of the digesta has to be increased from the very low pH of the abomasum; this is accomplished by buffers that are secreted by the pancreas into the first part of the small intestine. Important: The small intestine is where amino acids (from protein digestion) are absorbed into the bloodstream. Any nutrients that are not absorbed into the bloodstream are lost in the feces!

In the cecum, fiber can be fermented (digested) if it was not digested the first time in the rumen. That means ruminants have “two shots” at digesting fiber! Fiber digestion in the cecum is also by microbes; no animals can digest fiber unless microbes are there to do it for them. The digestion is the same as in the rumen, and VFA’s are absorbed through the wall of the cecum into the bloodstream. These VFA’s provide energy for the animal.

In the large intestine, some fermentation occurs by microbes that live in the first part of the large intestine. As material passes through the rest of the large intestine, water is absorbed back into the animal’s body.

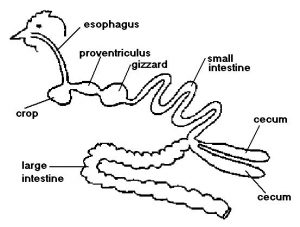

Poultry

Functions:

The esophagus transports feed from the mouth to the crop.The crop is a storage area where feed can accumulate if it is eaten quickly. Some lubrication can also be added to the feed while it is in the crop.

The proventriculus secretes hydrochloric acid, which is a strong acid that begins chemical digestion and also kills bacteria.

The gizzard contains small rocks that the chickens eat if they are in the wild. The feed is ground up in the gizzard. This is important for poultry in the wild, because they do not have teeth to chew their feed! Chickens in confinement are usually fed finely ground diets, so the gizzard does not play a vital role for them.

The small intestine is where digestion of everything but fiber occurs (by enzymes secreted into the small intestine). More importantly, the small intestine is where nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream. Any nutrients that are not absorbed into the bloodstream are lost in the droppings!

In the cecum, fiber can be fermented (digested) by microbes. Poultry in the U.S. are on low fiber diets, so this is not very important for their digestion. Some poultry have more than one cecum, and the plural of cecum is “ceca.”

In the large intestine, some fermentation can occur. Mostly what happens is that water is absorbed back into the animal’s body.